Note

The question of what constitutes “Americanness” in art has long interested me. It’s a somewhat self-serving interest, of course, since I’m an American composer. But it’s useful to think about. It was little more than 100 years ago that composers started writing music that sounded “American,” transcending the Eurocentric pastiches of earlier efforts. It’s a recent enough occurrence that one can still imagine different paths composers could’ve taken, could still take. In this spirit, Upstate Obscura is a kind of thought experiment set in the primordial ooze of the 19th century, when American artists mostly looked to replicate European models.

John Vanderlyn was one such artist—an ambitious painter from Kingston, New York, who spent years studying in Paris. Upon his return, he formed a grand (and misguided) plan to paint a gigantic panoramic scene of the palace and gardens of Versailles, and to exhibit the 360-degree work inside a rotunda of his own construction, in the hope of securing his reputation and fortune. But Americans had little interest in paying to see a replica of a fancy French palace; the work was simultaneously too realistic and too abstract to cause anything but befuddlement among the Kingstonians of its day. The panorama was a financial failure and faded into obscurity until the 1950s, when the Metropolitan Museum built a passageway in the American Wing to display it.

I stumbled on it there a few years ago (if one can speak of “stumbling” on a thing so massive). I was taken aback by its sheer scale, and also by the tricky way it uses perspective to convey even greater scale. But the overall effect of the painting is ambiguous; it’s hyper-detailed, yet curiously abstract; perfectly utopian, but with a sombre, melancholy cast. The light in the painting is a flat upstate New York light, and the viewer feels alone in it, ignored by the well-dressed spectators milling about. In taking on a quintessentially French subject, Vanderlyn somehow came up with something that feels American; it seems to regard Versailles at a bemused distance, with that characteristically American distrust of anything unnecessarily fanciful. As a New Englander who has never been to Versailles (Vanderlyn’s intended audience, after all), I identified with this out-of-placeness.

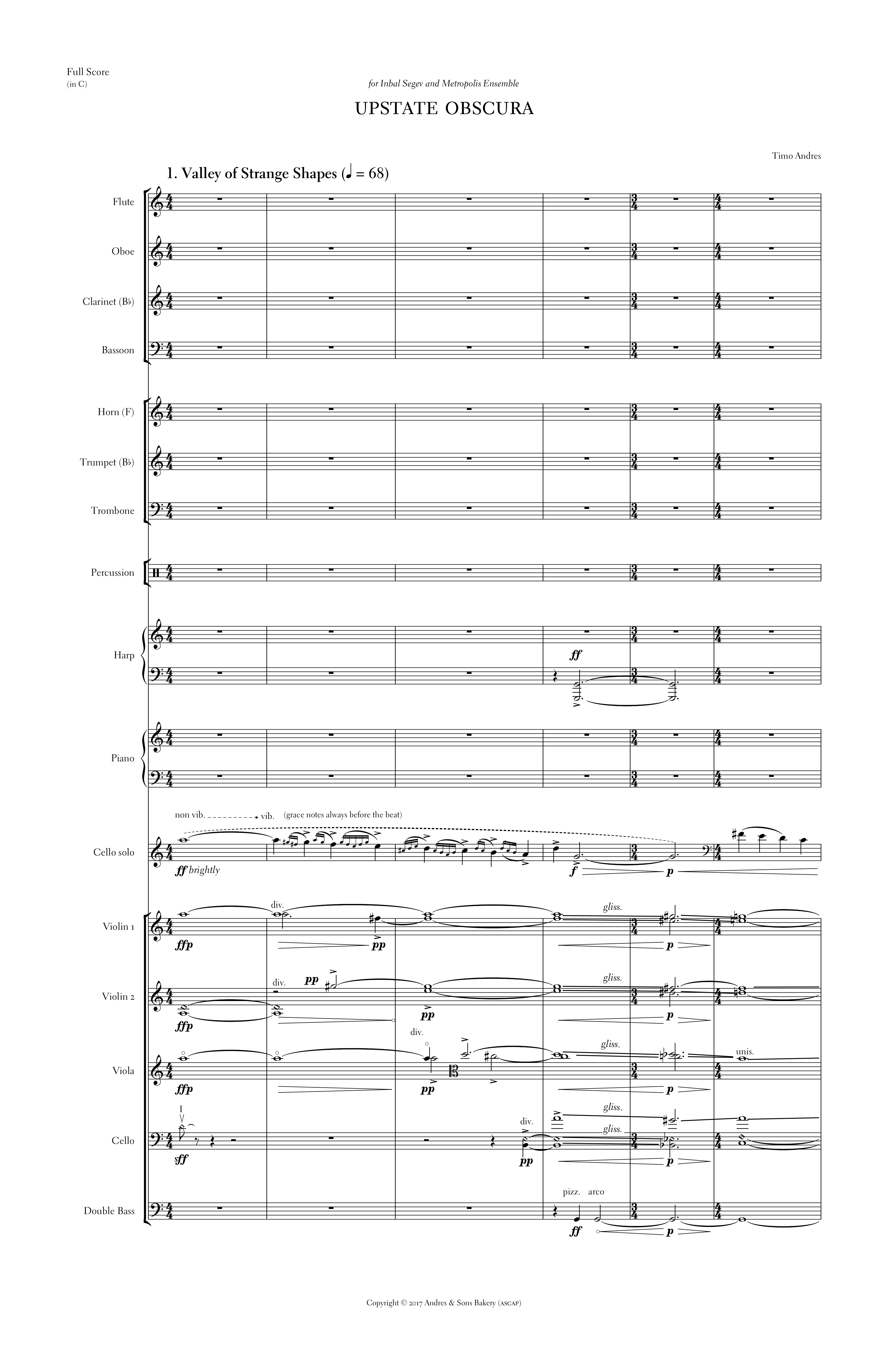

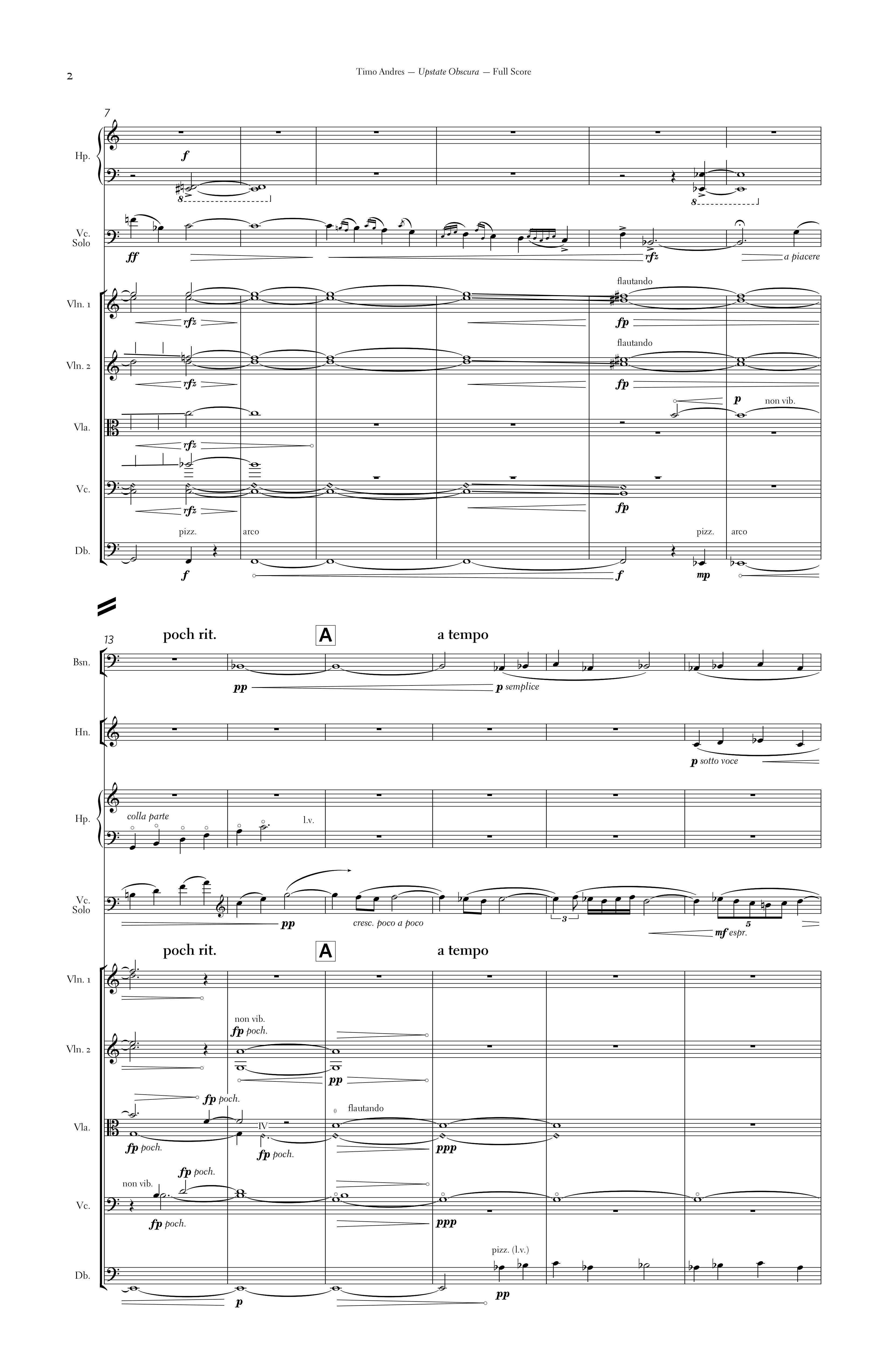

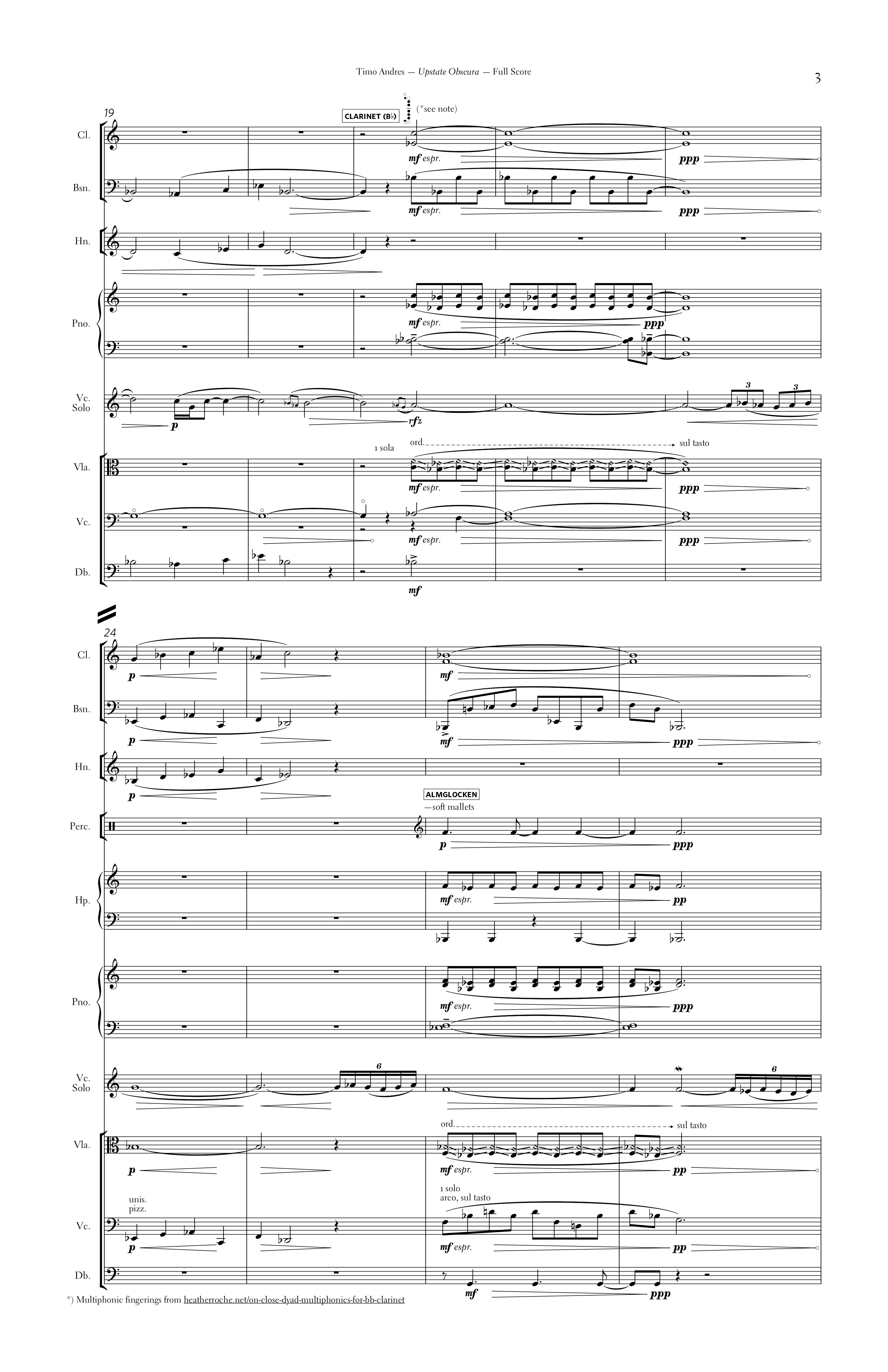

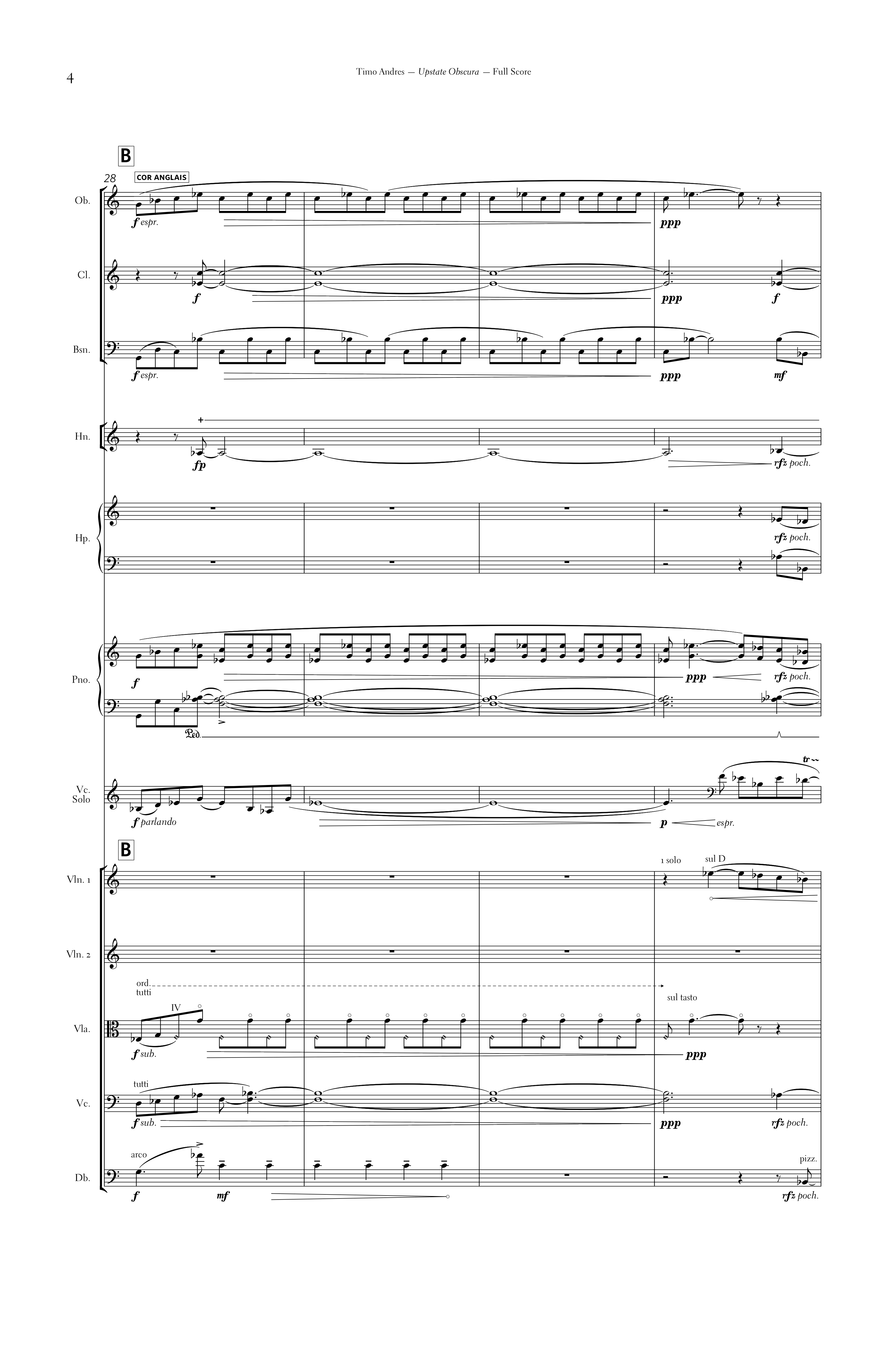

It was that uncanny sense of contradiction and tension in the painting that started me thinking about it as the subject for a piece of music. My plan was to start with fragments of musical ornament from the French Baroque tradition—like loose chunks of masonry—and stretch them out until they no longer felt like ornaments. All the melodic material in Upstate Obscura is generated this way. Each movement takes those stretched-out fragments and points them in different directions; I wanted to use register, and transitions between registers, as a way to translate the forced perspective of the panorama into a sonic illusion of physical space. The solo cello moves through these registers, just as a viewer might explore a virtual world—at times wandering, at times with purpose.

The first movement, “Valley of strange shapes,” finds the soloist moving slowly down a grand, sweeping staircase, past stylized musical objects played by the orchestra. The second finds the same protagonist lost in a topiary maze, or hall of mirrors; the music keeps restarting, turning back on itself, refracting into smaller reflections. “Vanishing Point,” an extended coda, turns its gaze upwards, towards an indistinct horizon.

Listen

Purchase

Upstate Obscura score, print edition

Upstate Obscura score, PDF edition

69 pages, 11×17 format. Includes full score only. Parts are available for rental; please email rentals@andres.com for a quote.