Note

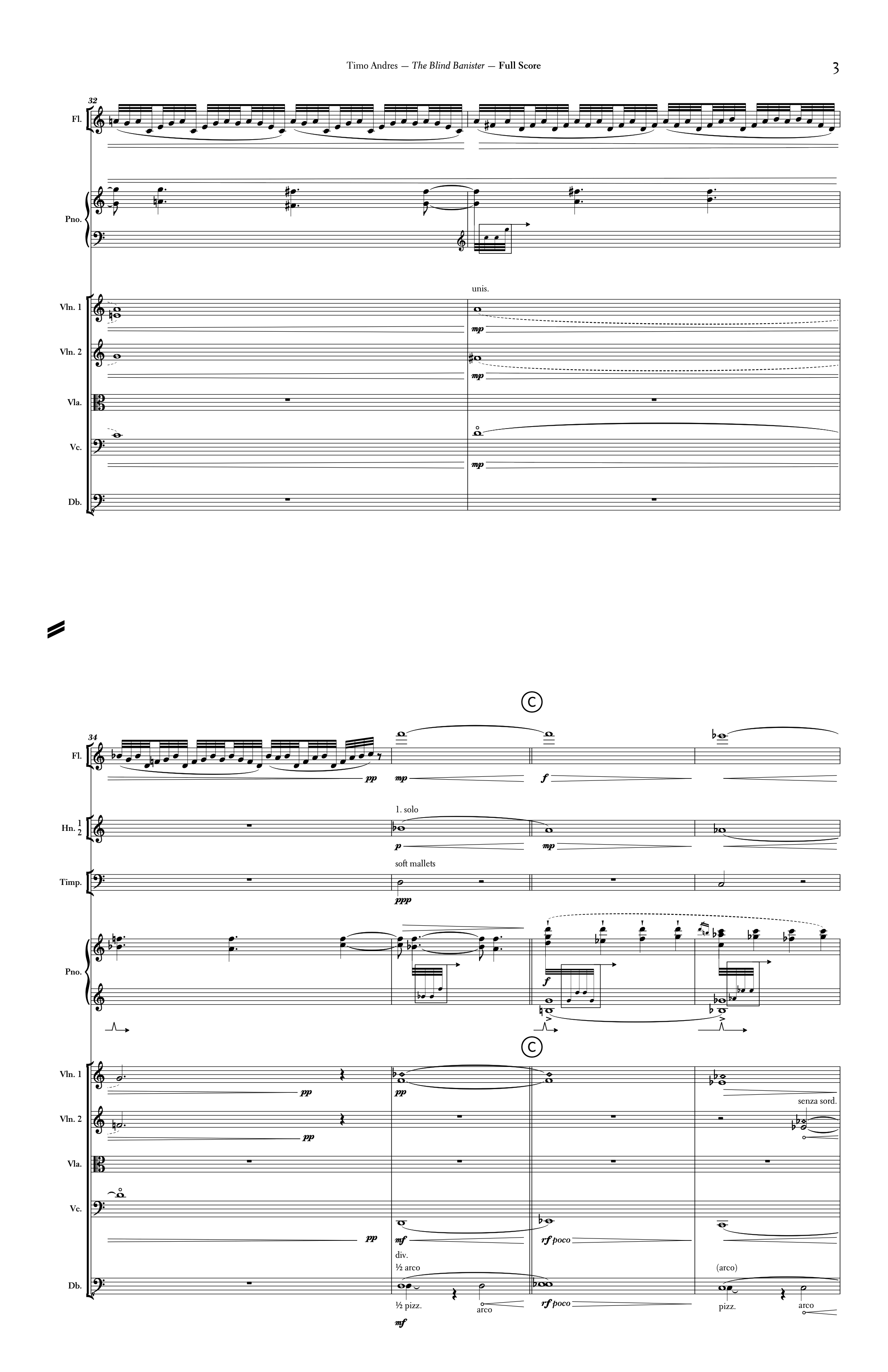

Solo piano introduces the main theme of The Blind Banister: two descending scales, one the melody and the other (lagging behind) the accompaniment, creating little rubbing major-second suspensions against each other with every move. This “Sliding Scale” is presented over and over, forming the basis for movement of continuous variations, constantly revising themselves. Orchestral layers pile up around the scale, building dissonant towers out of those major seconds. One last, long downward scale gathers enough momentum to launch the second movement scherzo, “Ringing Weights”.

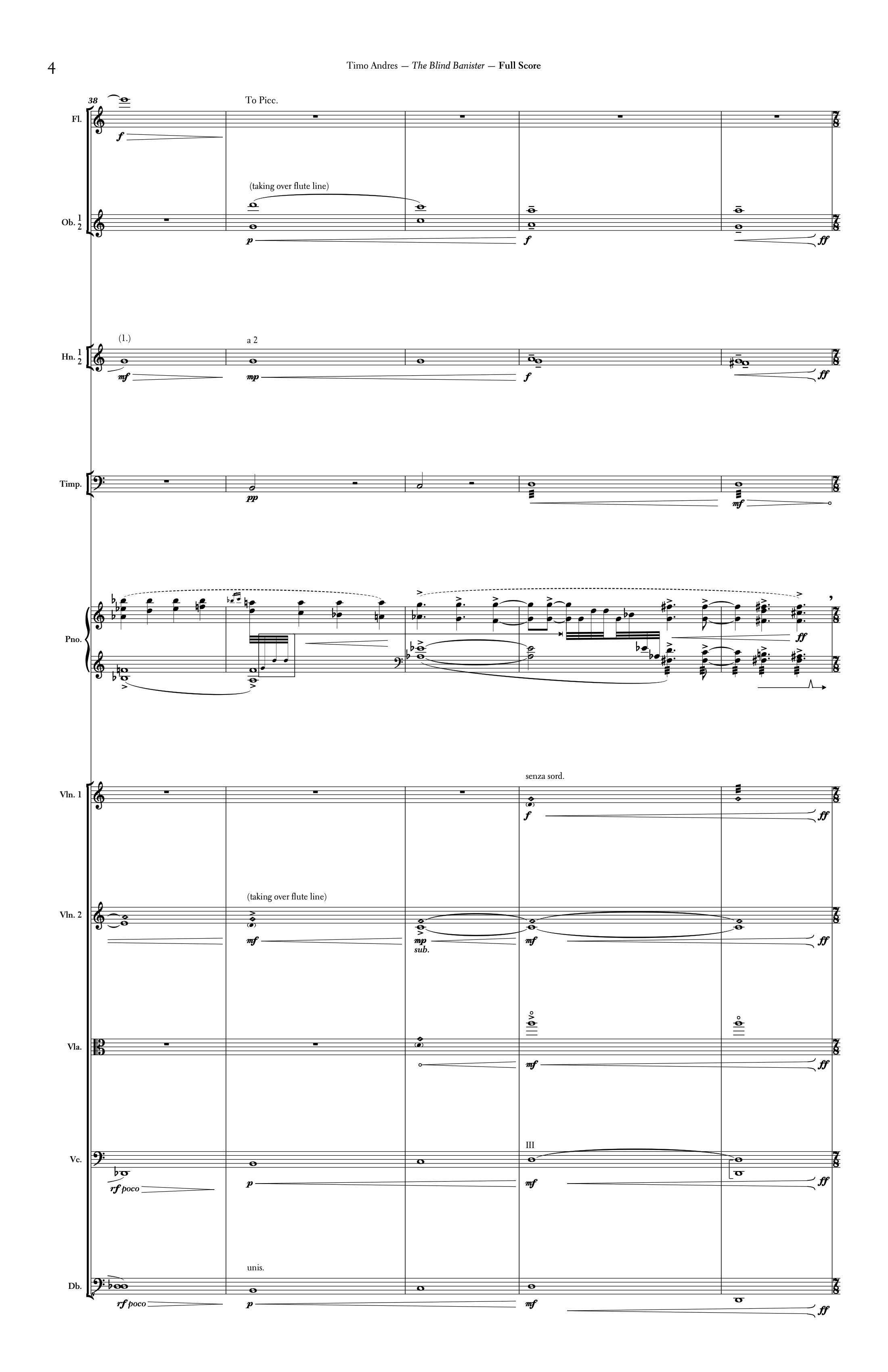

Here, the downward scale is transformed into a propulsive motor in solo strings, driving bright cascades of chromatic chords in the solo part. This movement is also made from varying modules, each increasingly elaborate—though this time, each successive module descends a step, the scale theme subverting the structure of the piece, trying to push it inexorably downwards.

The piano works hard to reverse this process in a trio section, trading a stumbling, step-wise melody with gentle orchestral echoes of the ringing chords from the scherzo. As the piano music lurches to its feet, it grows progressively more boisterous, and the steps move faster, whirling themselves into a return of the scherzo material, this time with full orchestra, the main theme in pounding timpani.

Orchestra suddenly falls away, leaving the pianist to wrestle with the two basic elements of the piece—rising and falling. Arpeggios leap up and over each other, unbound from any meter, vaulting through the harmonic atmosphere before plunging down to the lowest E. As the arpeggios begin to trace more regular patterns, the orchestra drifts back in with another long scale, descending step by step, introducing a richly-harmonized Coda, really a super-compressed recapitulation of the first movement, before the piano finally rushes off into an ambiguous future.

With Jonathan Biss and Joshua Weilerstein, after a performance of “The Blind Banister” at Caramoor by Orchestra of St. Luke’s.

The Blind Banister was written for and dedicated to pianist Jonathan Biss. Jonathan had asked me to compose a new concerto to be programmed alongside Beethoven’s second—a tall order. Beethoven gave this early concerto a kind of renovation in the form of a new cadenza, 20 years after writing it (around the time he was working on the Emperor concerto). It’s wonderfully jarring, in that he makes no concessions to his earlier style; for a couple of minutes, we’re plucked from a world of conventional gestures into a future-world of obsessive fugues and spiraling modulations. Like any good cadenza, it’s made from the same simple gestures which comprise the rest of the piece—an arpeggiated triad, a sequence of downward scales—but uses them as the basis for a miniature fantasia.

The Blind Banister is, in a sense, a whole piece built over this fault line in the Beethoven, trying to peer into the gap. I tried as much as possible to start with those same extremely simple elements Beethoven uses; however, my piece is not a pastiche or an exercise in palimpsest. It doesn’t quote or reference Beethoven. There are some surface similarities to his concerto (a three-movement structure, a B–flat tonal center) but these are mostly red herrings. The best way I can describe my approach to writing the piece is: I started writing my own cadenza to Beethoven’s concerto, and ended up devouring it from the inside out.

The piece was a finalist for the 2016 Pulitzer Prize.

Listen

Purchase

-

The Blind Banister score, print edition

-

The Blind Banister score, PDF edition

62 pages, 11×17 format. Includes full score only. Parts are available for rental; please email rentals@andres.com for a quote.