David Allen’s article in this weekend’s New York Times looks at “sequel” compositions, a topic well worth exploring. I’m using “sequels” to mean: pieces written explicitly as companions to preexisting, often well-known, works. The article, in which I’m quoted a couple of times, portrays sequels as a pernicious programming trend initiated mainly by conservative administrators, afraid to scare off their audiences with anything truly “new”. But I think the real story is something quite a bit more nuanced.

When I was just starting to write music, the impulse grew out of my piano playing. My early pieces were imitative of the music I admired and knew best: Brahms, Ravel, Prokofiev, Beethoven, Copland. This is how any anybody starts writing music—pick a template you like and fill in your own notes. As my knowledge of the world (musical and otherwise) increased, so did my confidence to start designing my own templates, taking charge of the bones my pieces.

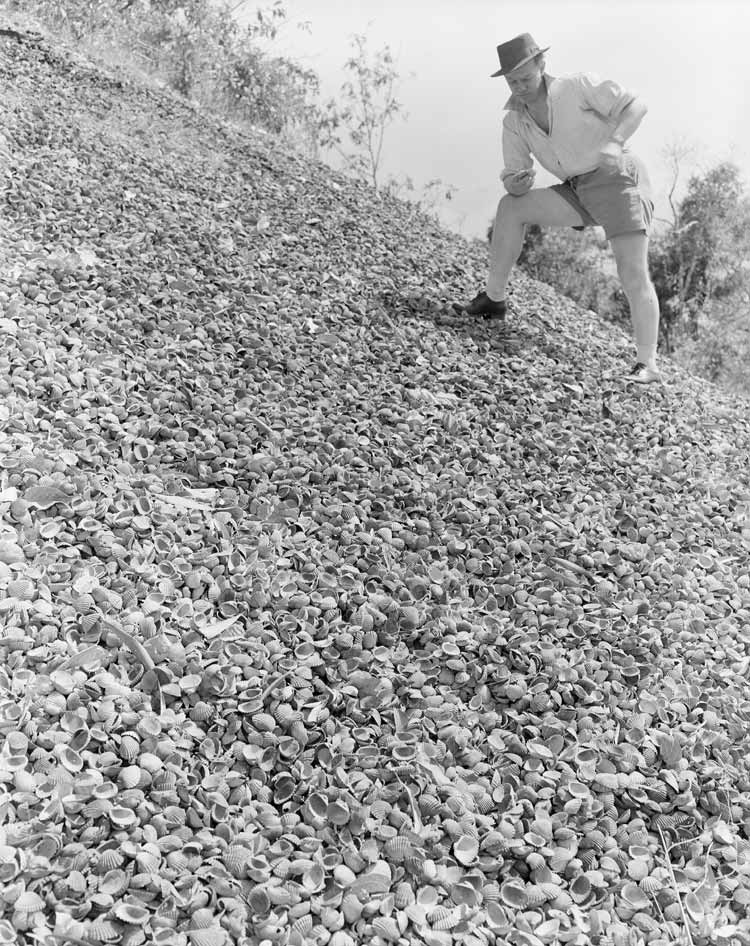

I’ve always found this process extremely interesting—the transformation of raw materials drawn from the great heap of music history into something totally new. So writing musical companions was something I originally did of my own volition and became somewhat known for, which resulted in commissions to write more such pieces. As present count, 19 of my fifty-something pieces have historical antecedents, beginning 10 years ago with I Found it in the Woods, which takes two chords from Brahms’s A major violin sonata as its generative material. I’ve since used several different compositional processes to refer to, learn from, or simply have a good time with preexisting music: Austerity Measures and I Found it by the Sea work backwards, finding their way to the source material through layers of my own variations; my “re-composition” of Mozart’s Coronation concerto imposes my own music directly on top of its source; the Piano Quintet and The Blind Banister abstract Schumann and Beethoven, through oblique structural references rather than outright quotation. Writing these pieces has not been an exercise in pastiche or postmodernism, but rather an integral part of my compositional development—investigating distant connections, filling in the space between.

I also think the article didn’t give a true sense of what it might be like actually to write such a piece of music. Simply working in the classical music tradition is, for me, a great source of material (by which I mean: writing detailed instructions in a document which is given to performers, who then follow the instructions, producing a version of my piece). And part of this is acknowledging that people have been making music in this strange, roundabout way for a thousand years. So it’s understandable to want to look backwards once in awhile, maybe now especially, as the history-renouncing teleology of Modernism recedes.

But is it a kind of pandering? I don’t think it’s pandering to think about your audience now and then (and I know that by saying that, I’ll have lost a certain number of the people who read this). Any music can pander—if not to audiences, then to grant panels or tenure committees. Simply putting new music on the same program as Beethoven may not be enough to convince audiences of their commonality; a well-considered response can show without telling.

The context for my quote in the Times about nearing “the end of my rope” was in discussing whether or not these commissions have become a hackneyed programming trend. As with all trends, there are of course thoughtless and bad examples. Not every living composer can respond to every long-dead one and expect to illuminate. Perhaps not every masterpiece of the past demands a response. Winking quotations or musical inside jokes are a blind alley, a self-appreciative pat on the back. And an overdose of nostalgia for lost musical idylls tends merely to remind us who was excluded from the supposed “golden age”—women and minorities, who are still hugely underrepresented in contemporary music commissioning.

David Allen’s article failed to differentiate among the forms of responses composers have written, as well as the conditions under which they might succeed or fail. If composers were in fact being talked into writing certain kinds of pieces by new-music-wary orchestral administrators, as the article seems to imply, this would indeed have a chilling effect on creative freedom in our field.

But in my own experience, this couldn’t be further from the case. For The Blind Banister, the pianist Jonathan Biss approached me with an idea for a project that he had devised independently (the Beethoven/5 commissions). So I had one more piece of information than I usually do when beginning a piece: the soloist, the instrumentation, the duration, plus Beethoven’s second concerto. A handful of orchestras signed on to commission it (on the strength of their faith in Jonathan, more than anything else), the piece was premiered, another small handful of orchestras decided to program it (one, audaciously, Beethoven-less!)—and so a new piece of music makes its tentative way in the world.

Jonathan Biss will respond with his perspective as a performer and commissioner later this week; watch this space.